Athens, or the Fate of Europe

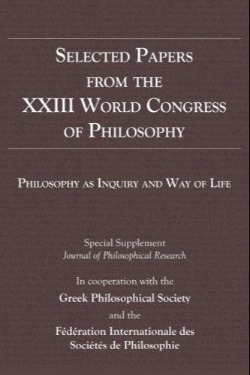

Jos de Mul. Athens, or the Fate of Europe. Journal of Philosophical Research. Special supplement: Selected Papers from the XXIII World Congress of Philosophy. 2015: 221–227.

ABSTRACT: In his essay ‘The Idea of Europe’ George Steiner claims that European culture derives from “a primordial duality, the twofold inheritance of Athens and Jerusalem”. For Steiner, the relationship between Greek rationalism and Jewish religion, which is at once conflictual and syncretic, has engaged the entire history of European philosophy, morality, and politics. However, given this definition, at present the United States of America seem to be more European that ‘the old Europe’ itself. Against Steiner, it will be argued that in order to fathom the distinctive characteristic of European culture, we have to take a third European tradition into account, which is inextricably bound up with Athens: the tradition of Greek tragedy. If we may call Europe a tragic continent, it is not only because its history is characterised by an abundance of real political tragedies, but also because it embodies, as an idea and an ideal, a tragic awareness of the fragility of human life. Instead of reducing the ‘idea of Europe’ to a financial and economic issue, Europe should remain faithful to this idea and ideal.

ABSTRACT: In his essay ‘The Idea of Europe’ George Steiner claims that European culture derives from “a primordial duality, the twofold inheritance of Athens and Jerusalem”. For Steiner, the relationship between Greek rationalism and Jewish religion, which is at once conflictual and syncretic, has engaged the entire history of European philosophy, morality, and politics. However, given this definition, at present the United States of America seem to be more European that ‘the old Europe’ itself. Against Steiner, it will be argued that in order to fathom the distinctive characteristic of European culture, we have to take a third European tradition into account, which is inextricably bound up with Athens: the tradition of Greek tragedy. If we may call Europe a tragic continent, it is not only because its history is characterised by an abundance of real political tragedies, but also because it embodies, as an idea and an ideal, a tragic awareness of the fragility of human life. Instead of reducing the ‘idea of Europe’ to a financial and economic issue, Europe should remain faithful to this idea and ideal.

First of all I like to thank the organizers for their invitation to join this symposium on Art and Cultures. As a tribute to the magnificent city of Athens and its inhabitants, I will talk about the relationship between European culture and the art form that is inextricably tied to the city of Athens: Greek tragedy. The thesis I will defend is that European culture distinguishes itself from other world cultures, and in particular from North-American culture, with which it shares both its Christian and its scientific worldview, by its deeply tragic character. This claim, I will argue, is neither a pessimistic nor an optimistic one, because tragedy is beyond this simple dichotomy. If I claim that Europe is a tragic continent, I refer both to its grandeur and pitfalls.

My talk consists of two parts. First, in a critical discussion with George Steiner, I will address the question of the identity of European culture. In the second part I will relate this identity to Greek tragedy.

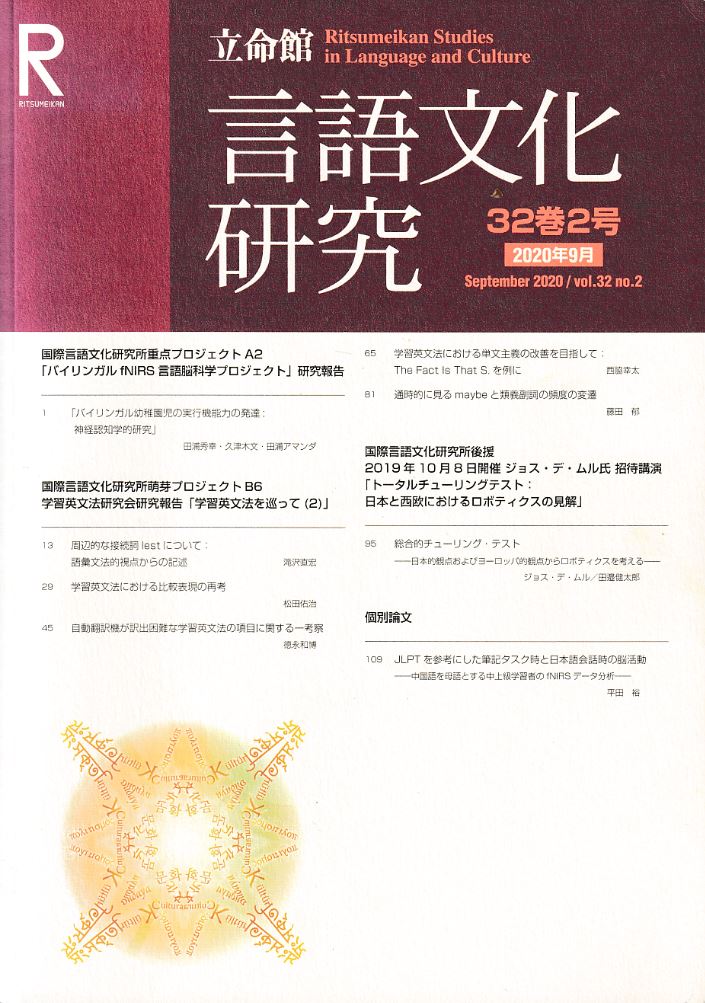

国際言語文化研究所後援

国際言語文化研究所後援

Jos de Mul. Uncle Sim Wants You! Playful Warfare.

Jos de Mul. Uncle Sim Wants You! Playful Warfare.  Vanaf de derde druk verschijnt

Vanaf de derde druk verschijnt