Jos de Mul & Alberto Romele. Imagination, Images, and Imaginaries. A Dialogue with Jos de Mul, In: José Higuera Rubio, Alberto Romele, Sarion Ridrighiero & Celeste Pedro (eds.) From Wisdom to Data. Philosophical Atlas on Visual Representations of Knowledge. Porto: University of Porto Press, 2022, 35-44.

1. Imagination

Alberto Romele: The first part of this dialogue is focused on the notion of imagination. It is from your work (to which I would add the work of Paul Ricoeur) that I have learned that (1) imagination is not creatio ex nihilo, but rather recombination and (2) imagination is always technologically (and digitally) externalized. I am thinking, for instance, of your 2009 article “The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Recombination”. Could you tell me a little bit more about your understanding of imagination, its relationship with technology, and the importance you attribute to authors like Kant, Dilthey, and Cassirer in your research?

Jos De Mul: I have been writing a new book on database for some time now. The reason why the book is still not finished is that it completely went out of hand in a way when I rediscovered Cassirer. I wrote an additional chapter on Cassirer and it's about 90 pages now, so it's almost a complete book on Cassirer now. But it was important for me because all things fell in that place. The first chapter of my book is called “The Medialization of Experience”. And I start with Kant in the book.

And what is the medium for Kant? The medium is the human reason. However, there is in Kant a presupposition that all people have the same apriori forms. This idea became a problem very soon after, because of the historicization of the worldview in the 19th century. The second person I discuss after Kant is Dilthey. The first thing Dilthey says is that these apriori are historically and culturally variable. We live in different worlds, literally: not in the sense that we look differently to the same world, but our phenomenological worlds are really different. Furthermore, according to Dilthey, Kant is focusing too much on theoretical reasoning. But knowledge is not only natural scientific knowledge. We also have cultural knowledge. Human and social sciences (Geisteswissenschaften) apprehend the world in a different way than the natural sciences: human experience is a nexus of knowing, willing and feeling, and in each faculty, the bodily component is very important. Moreover, what Kant does not consider is that our thinking is not empty reasoning. It is always taking place in a natural language, and natural language is an external medium that influences the way we experience the world.

In summary, we could identify three elements in Dilthey’s criticism to Kant: first, the historicization of the apriori; second, what I call “vitalization” of the apriori — experiences are bodily experiences; third, externalization of the apriori. In my book, I show how in the in the 19th and 20th century, these three themes are becoming main themes, especially in continental philosophy. Hence, media philosophy is a kind of philosophia prima of the 20th century.

Cassirer further develops Dilthey’s threefold transformation of transcendental philosophy. Whereas Kant’s transcendental schemata” of the imagination are fixed a priori of scientific reason, for Cassirer there are multiple “symbolic forms”. Each of these symbolic forms imagine time, space and categories like causality i fundamentally different ways.

Cassirer started his career as a neo-Kantian, and the neo-Kantians were very focused, epistemologically, on natural sciences. But after he became a member of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg Cassir started to focus on other symbolizations of the world, like art, religion, mythology, technology, etc. These forms are historical and cultural in nature. However, already in Cassirer’s early, still neo-Kantian work on Einstein, we find the germs of his later philosophy of symbolic forms, Kant started from a universal apriori of space and time based on the mathematics of the Greek; Einstein, on the other hand, used new kinds of non-Euclidean mathematics, so it apparently contradicted Kant. But Cassirer made an interesting move. Kant was not wrong, he says. Well, maybe he was wrong in the sense that that he did not see the historical dimensions of our a priori. But Einstein supports Kant insofar as he showed that the way we experience the world is depending on our apriori forms — only these forms develop in time and his theory of relativity was based newly developed non-Euclidean ones.

Cassirer especially became interesting for my own project when I discovered his philosophy of technology. I never realized before that he had a philosophy of technology. Technology is not only the subject of Cassirer’s somewhat neglected article “Form and Technology” (1930), but also plays a prominent role in the second volume of The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms (1925). The book is about mythology and there, Cassirer argues , mythology is the first form of technology. Mythology tries to control the world like technology, only it's still a “wishful thinking”. Myths try to control the world by story. Myths represent an important step because a prehistoric hammer, for example, is kind of transitional object from mythology to technology because hammers were seen as instruments of the Gods, possessing and providing magical power to its users. But he says this also was the first notion of technology. A hammer is something you use to do something, and that's almost already the hammer analysis of Heidegger in Being and Time. I don't think this is coincidentally. Heidegger wrote a positive review of this book of Cassirer, emphasizing the practical dimension of it. Human reason is not sheer theoretical thinking, but it has to do with practice.

What is a symbolic form for Cassirer? Is a way to symbolize the world, a seeing as…. The same figure can be interpreted as a magical symbol, an aesthetic expression of the visualization of a mathematical function. Art, religion, language, law, and science belong to the most fundamental ways of symbolizing the world. Cassirer claims that these symbolic forms are universal, and universal means two things for him. They are universal in the way you can apply them to everything, so everything can become subject of language, religion, science, etc. But they are also universal, according to him, because you find them in all cultures. They are universal, but at the same time, they have many different manifestations. Every culture has a language. Every culture has a religion. Every culture has some sort of technology and science. But their manifestation is historically and culturally variable.

What I especially found very fascinating reading Cassirer is that according to him, there is a kind of evolution of symbolic forms. For him, everything starts in a way with mythical thinking. He says that's a kind of first a moment in time that human beings start to symbolize the world. So they are no longer just like animals reacting to external stimuli, but they are trying to grasp the world in a mental way. I mentioned already the hammer, which has a kind of ritualistic aspect. But the hammer is also a starting point for technology, and for science, as its use also brings along a notion of causality. Religion can be also understood as an evolution of the mythical thinking when it gradually starts with personifications of the powers of nature up to the notion of a god. For Cassirer, we still find this mythical element in modern thinking, for example, in technology. Technology still has a magical element in it. We hope to control the world with the help of technology; once we had magic hammers, now we have magic computers and magic algorithms, so to say.

In my book Cyberspace Odyssey (2002), I have also analyzed this magical aspect of technology: every advanced form of technology is like magic. The telephone is a kind of magical thing in two senses. First, because it's effective. I mean, it works. But on the other hand, is magic, because it's mystery. You don't really know how it works, it’s magic in that sense.

Although Cassirer argues that we can discern a pattern in the development of symbolic forms towards an increasing abstraction, progress is not guaranteed. In his last book, The Myth of State (1946), Cassirer says: if you look at Nazi Germany, you see that the idea of the political was taken over by a mythical thinking. Think of the mythology of the thousand-year empire, the magical figure of the leader, etc. Politics, which was originally a kind of emancipation from mythological thinking, and developed into an autonomous realm, so to say, falls back into magical thinking. And also technology, he says, was used by the Nazis in a very clever way: radio and TV and film in order to spread their mythical ideology. And so, these different symbolic forms, they have one origin, but they can always again intermingle. That fits in very nicely what you said in your discussion with Lemmens (see Romele’s article “The Transcendental of Technology is Said in Many Ways”, 2021). Indeed, the technological is a transcendental form, but there are many other transcendentals of technology. I introduce a term for it in my book, which is in the spirit of Cassirer, although he doesn't use the term himself, to summarize his position. I call it “transcendental perspectivism”.

A.R. Thank you Jos. And what about recombination? I mean, isn’t the very historicized, externalized, and embodied nature of human imagination also the reason of its recombinatory nature? Aren’t we always, precisely for these three dimensions (historicity, vitality, and technicity) “standing on the shoulders of giants” even when it comes to our most authentic creations? Don’t you think that digital machines, that seems more and more be able to observe regular patterns in our creative works, and seems increasingly able to imitate our most creative gestures, are demonstrating this? Should be afraid of it?

J.d.M.: In my opinion there is no reason for fearing the recombinatory nature of our imagination. The Ars (Re)Combinatoria consists of all possible (re)combinations, of which the vast majority does not exist (yet). Take the alphabet: only 24 letters, in that sense every past, future and possible utterance is ‘just’ a recombination of these 24 letters. Does this limit imagination? Think of Borges “Library of Babel”, dealing with a library consisting of all possible books of 410 pages, 40 lines, each having 80 characters, that is, 1.312.000 characters, written with the 25 characters of the Spanish language (22 letter, blank, dot, comma). The number of books then is 25 to the power 1.312.000 (251.312.000). If we consider that according to cosmologists the universe consists of 10 to the power 80 (1080) atoms, this number is negligible compared to the number of books in the library of Babel!

There is also a “Library of Mendel” (Dennett), which combines all possible genetic combinations. Interesting point: according to Dennett not all combinations are logically possible (existing and not-existing at the same point), not all logically possible combinations are physically possible, not all physically possible combinations are chemically possible, not all chemically possible combinations are biologically possible (a flying horse: herbivores do not take in enough energy to fly), not all biologically possible combinations are historically possible (path dependency: think of descendants of extinct species like dinosaurs or the dodo).

A.R.: This is an interesting point, because Dennet’s perspective seems to be more realistic. It considers not only the possibilities in principle, but also the “affordances”. In principle, many planets in our galaxy could host some form of life. But if you look at the affordances, the possibilities are less and less, but everything become also much more realistic. Maybe my question here is: if we look at our use of database and algorithms, especially for scientific discovery and technological innovation today, could we say that we are leaving the “Borges age” and entering the “Dennet age”? In other words, are we more realistic than ten or twenty years ago about the possibilities and the limits? It's a bit like the infinite monkey theorem, which is the claim that a monkey typing random keys on a typewriter keyboard for an infinite amount of time will almost certainly type any given text, such as the complete works of William Shakespeare. You certainly know that someone has run the experiment and it did not work. In a month, the monkeys produced nothing, but five total pages largely consisting of the letter "S". Moreover, the lead male began hitting the keyboard with a stone, and other monkeys followed by smearing it. What I mean is that Dennet does not deny the recombinatory principle, but he makes it more real and less giddy than Borges'.

J.d.M. Indeed, I think we are in the very first stage of the Dennet’s age. Take, for example, genetic engineering, which is putting this idea of (re)combination into practice. I also think about mass customization: now you order a specific car and then they make it with the engine you like the most, the radio system and the color etc. you wish.

Cassirer says symbolization in a way comes down to the use of metaphor. And of course, the use of metaphor is imagination. We are back to imagination. So, metaphor is a kind of imagination in which we symbolize the world. If we say “the heart is a motor” we design a new worldview in a way. We know how important metaphors are. Well, these are conceptual metaphors. We use them to grasp the world. Well, the idea Catherine Hayles introduced, is that there are also material metaphors that do something in the world. If we replace a defective heart with a mechanical equivalent, the conceptual metaphor – the mechanistic worldview - becomes a material one. My former PhD student Marianne van den Boomen has applied this idea to computers in her thesis Transcoding the Digital (2014). For her, computers are material metaphors because you can do something in the world, for example, if you take a computer program that is used by a biologist, geneticists for manipulation of genes. For example, if we call a CRISPR-Cas9 a programmable scissors , we have a conceptual metaphor. But by connecting your computer to a DNA synthesizer, it becomes a material metaphor. You can change reality with it. I would say that's the moment that you enter the Dennet age. In the case Borges, it's still a very interesting play of imagination and artwork.

I want to add one more thing, which has to do with monkeys, evolution, and self-organization. If you look at this, these monkeys out there, the idea is if they have time enough, they can write a complete works of William Shakespeare. Well, you can also be a little bit more modest and say, how long will it take before they will write one single sonnet of Shakespeare? Then it still will take many billions of years before the first sonnet of Shakespeare will appear, that is: much longer than the ca. 13 billion years our universe exists. So the idea that completely at random machines would produce something like a sonnet is neglectable. Well, that's hardly possible. That is, I think, also the message of Borges’ story because the library contains all possible books. Also, the book with the ultimate truth of the universe. But you will never find it because the number of books in the library is literary hyper-astronomical, bigger than the number of atoms in the universe. So there must be another principle as well. And that is self-organization.

Richard Dawkins defends a very mechanistical notion of evolution: for him, it is just random mutations. And then he also mentions this example of the monkeys and he says we can speed it up by, for example, you do the type randomly and as soon as one of the letters of the sonnet is in the right place, you fixate it. In a couple of weeks, you will have the complete sonnet instead of billions of years. This is a principle of self-organization.

And there is a self-organization also in ‘biological databases’, also known as organisms. From an evolutionary perspective, biological databases are not fixed, but adaptive systems that change because of their interaction with the environment. But it also applies to cultural databases like a natural language. Think of the database of language which in the age of globalization adapts itself to the multicultural environment (in the Dutch language, for example, many new words entered from the Indonesian and Surinam languages (during the colonial period), Turkish and Moroccan (because of the multiculturalization), and above all English (because of the global domination of the Anglo-Saxon culture)). This opens new paths in the database, novelties in the vocabulary, grammar, and style.

I think the novelty often emerges when two different symbolic forms merge. You can use technology in many different cultural form contexts, so to say, and so you can use the computer to produce art, you can use it as an economical instrument, you can use it as a scientific tool. And that's also with AI algorithms, of course.

2. Images

The second part of this dialogue is devoted to images, and in particular diagrams. For me, the link between imagination and images, diagrams in particular, is obvious: diagrams are externalizations of knowledge that do not merely represent knowledge, but “operate” it as well. In this sense, they are imaginative — where imagination is mainly understood as “ars recombinatoria”. If we consider medieval diagrams, are we then dealing with proto-imaginative machines? After all, what is being done today is in some way a continuation by other means of what Ramon Llull and many others were already attempting to do in the 13th century. Another point: before this dialogue, I have asked you to choose one of the images from our catalogue. You chose this one. Why?

J.d.M.: Yes, I chose this image and then I read Michael Stolberg’s Uroscopy in Early Modern Europe (2015). According to him, urine functioned as data (dead matter, extracted from body), which made it possible to predict and control. Objective, visual evidence instead of subjective feelings! Uroscopy offered visual evidence of long-held beliefs about the body. It was widely presumed, for instance, that illness could result from morbid matter collected and settled within the body. Cloudy urine was thought to provide evidence of this phenomenon. The practice only began to lose favor altogether by the nineteenth century, and Stolberg calls this decline as the result of “uroscepsis”. Interesting parallel with data: Stolberg states that nowadays it seems absurd to think that we can predict and control solely on the basis of the color of urine. Nowadays we magically believe that we can predict and control solely on the basis of data (another case of dead matter extracted from the body: objective, visual evidence).

A.R.: What I like about diagrams, is that they can be observed or “read” according to different levels of abstraction. There is, for example, at primary level, which I would say is almost chromatic. For instance, your image of the urine hit me, first of all, because of the color. And that's it. Second, there is a symbolic level in which I recognize forms and in case I can attribute a meaning to them. Finally, there is a diagrammatical level in which I “use” the image as an instrument, a sort of combinatorial and recombinantorial machine, so to speak.

J.d.M.: I think again to Cassirer in the sense that he says it is possible to have one visual Gestalt – like the line I’ve mentioned before - and interpret it in many different ways so connect it with different meanings. Maybe this is both the weakness and the richness of the image: you can always have new interpretations of the image.

A.R: On the one hand, you can interpret it in different ways. I think it depends on the context. But on the other end, images like texts have their legitimate and illegitimate interpretations. In the case of diagrams, I can make them work as diagrams, as (re)combinational machines. This is not the case of other images. I cannot take a painting by van Gogh and use it as a diagram. Diagrams I can use them both as paintings, let’s say, and as diagrams.

J.d.M.: Indeed, a diagram is something in between an image and a mental idea. What is interesting in Cassirer for me also that he demonstrates that science starts very concretely. There are concrete objects, and you try to do something with them. You have a metal, you want to melt it, or you have a tree, and you want to make a house of it, you try to understand and deal with concrete objects. Originally, mathematics was also used to do that. For example, geometry was often used for the measuring of land. So, it was originally used for very concrete purposes. According to Cassirer, the greatness of Leibniz is that he saw mathematics as no longer related to the concrete world, but to possible worlds. And in a way, diagrams are about possible worlds. They do not give one specific image of the world, but different possibilities. Diagrams are not representations of the reality, but simulations of it, not showing what is, but what is possible.

Normally, images for Cassirer are the lowest part in knowledge because they just represent reality. Diagrams are already an attempt to do things more abstract, but still in the realm of the image. So yeah, they are already transcending the image in a more spiritual way, in a more conceptual way, but they do it still in the language of the image. And that's why I see them as a kind of transitory, phenomenon. Mathematics, the language of modern science, is the most abstract type of symbolization.

A.R.: Technically, the image of the urine is not even a diagram. It is more like a map, a cartography of the different diseases and the different relations between diseases and urine colors.

J.d.M.: Yeah, but it is already database-like: you have two different elements, they are all ordered in a certain way and the colors are from light to dark, so to say. There is an organization. When you ask what a database is, I think there are three elements in it. First, a collection of elements. Second, a model of organization of those elements (e.g. a hierarchical, network or relational database model). Third, the word may refer to a database management system, a concrete application of a database, with specific roles and rights to insert, browse, change and delete data (e.g. the database used by Amazon to manage their goods, customers and logistics). A classical telephone book is already a database: you have different elements (all the names of the telephone users), and it has a model of ordering (alphabetical order). It is a system, in the sense you can use it to look for the telephone number of a person, but it is also not very flexible. A little bit like the urine boxes because you cannot recombine them in many ways. A second way to do it is to make an index card box with telephone numbers. It is more flexible because you can order it in different ways (by name, postal code, number), insert or delete cards etc. But it is still time-consuming to re-order such a database. The third step is the database in the computer program because if you have an Excel sheet, you can change it with one click. You can change the database. You can order by name, street address, city, postal code, etc. And so, you say that this diagram or map is a first step. Like the telephone book is a primitive step on the way to the flexible database. The most flexible form is the relational database, which enable you to combine and recombine all atomized data elements. Borges’ Library of Babel actually is such a relational database (you can find several version of it on the web). The relational database is in a way the concretization of the ideal of knowledge of Leibniz.

3. Imaginaries

A.R.: I would like now to go to the last part of our dialogue, which is devoted to imaginaries. In a 1999 article, you introduced the notion of “Informatization of the worldview”. This informatization represented for you an alternative to the previous mechanistic worldview. Do you think that something has changed in the last 20 years? I was wondering if the way we deal with meaning today is quite different. Meaning is today a matter of emergence from chaos, while the chaos is still present and often represented. Meaning is a matter of probability. In the informational age, meaning was much more “linear” I would say. Chaos was feared and eliminated. Today, we show it; so, meaning is always partial in comparison to the chaos that is around. A couple of years ago I wrote an article about this, titled “The Datafication of the Worldview” (20xx), which was a kind of integration in this direction to your previous reflections on the topic.

J.d.M.: I see your point, but I think basically the origin of informatics was the same. Look at Shannon. Shannon was an engineer. For him, the problem was, for example, when you want to transfer a message to a telephone line or another telegraph line, that there is a lot of noise in the transfer of the data, so there is a lot of chaos. And what he wanted to do was to create order in the chaos. This was quite simple in that time, you could say, because the chaos was in one line, the telephone line. Today, we have a lot of data, and we look for interesting patterns — and maybe, like Shannon we don't know what we want with it, but we are just interested in the efficient syntactical patterns.

A.R.: Still, I would say that today we have a higher toleration for chaos. I mean, look at Shannon. The point was to eliminate noise for him. He wanted a message to arrive as clear as possible from point A to point B. Today we accept a certain degree of chaos, and we accept it as part of this world.

J.d.M.: Of course, we are dealing today with a statistical notion of truth. But this notion was already introduced by quantum mechanics in the beginning of the 20th century. Einstein could not accept it: he famously said that God does not play dice with the universe. So, I am wondering whether we really are accepting chaos so much more. I think we are forced in a way because we are forced to accept that the world is not that organized as we would like to have it. And that's a kind of mythical wish that the world is organized. During the Human Genome Project, it turned out that only about 2 percent of the DNA has coding capacities. And the other 98 percent, they called it junk DNA. This 98 per cent is maybe remainders from our evolutionary past. Waste that is still in the cell, but which has no use anymore. Well, later they discovered it was not chaos at all because big parts of it have regulatory functions. And so it was a big relief. Fortunately, it's not chaos!

The Master Algorithm (the idea introduced by Pedro Domingo in his 2015 book) will always remain a fantasy. But of course, fantasies can help you. So, they have a function. An imaginary function!

A.R.: I am wondering about the role technology plays in the construction of these fantasies or imaginaries. I mean, on the one hand technology is the object of them; on the other, it is the subject, in the sense that it creates new imaginaries, expectations, hopes, and fears to cope with reality. Maybe we need, as you said, an imaginary of the master algorithm even more than the master algorithm itself!

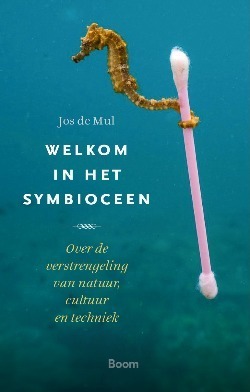

Vanaf de derde druk verschijnt

Vanaf de derde druk verschijnt